Keeping Options Open: Why UK Tech Needs EMI Reform

Today, Startup Coalition launches a new report calling for EMI reform ahead of the Autumn Budget.

The following data and analysis is taken from our report released today, Keeping Options Open. Find the full report here.

Imagine you’re building a startup in the UK, trying to attract world-class engineers or commercial talent.

You’re up against corporate giants – fast-scaling (and often American) competitors offering generous compensation packages and the promise of Silicon Valley-style riches.

Ping-pong tables and unlimited holiday won’t cut it. What you really need to attract talent is stock options.

Stock options offer elegant simplicity: if your team collectively builds something extraordinary, everyone reaps the rewards. It’s a powerful alignment of interests, where company success becomes personal success. And we know that the wealth generated often finds its way back into the ecosystem, creating a flywheel of angel investment, new ventures, or scale-up expertise.

For startups that can’t compete on salary with global behemoths, equity compensation isn’t a perk. It’s essential. Tax-advantaged share option schemes are a smart way to level the playing field between scrappy challengers and cash-rich corporations.

The UK was one of the frontrunners. Back in 2000, when the UK introduced the Enterprise Management Incentive (EMI) scheme, it was world-leading. It was introduced as the Government recognised that the ‘main barrier to growth experienced by smaller high-risk start-up businesses was a lack of highly qualified and motivated key employees.’ In the intervening years it has become the backbone of the UK’s startup ecosystem, helping British companies compete globally for top talent.

But while global competition for startups has changed, EMI hasn’t.

Startups competing in Deeptech and AI need more capital to succeed than ever before, and companies that used to take eight years to reach 500 employees now do it in five. Yet EMI eligibility still uses outdated employee ceilings and asset caps that don’t reflect how fast companies grow today or how much capital they need to do it.

When a startup raises a major funding round that pushes them over the £30 million asset cap, they lose eligibility to issue further EMI options at the precise moment they need it most, during rapid hiring to support their growth. A company that closes funding on Monday may find itself unable to offer competitive equity packages to candidates starting on Tuesday.

Meanwhile, HMRC has adopted a rigid interpretation of the rules, especially around board discretion in exit scenarios, which does not reflect the change in company exit options over the last 10 years. This creates confusion, legal risk, and makes it harder to reward the people who will likely go on and build the next British success story.

We surveyed dozens of founders and operators for our new report, Keeping Options Open. The feedback was surprisingly consistent. EMI works brilliantly until suddenly it doesn’t.

We found that:

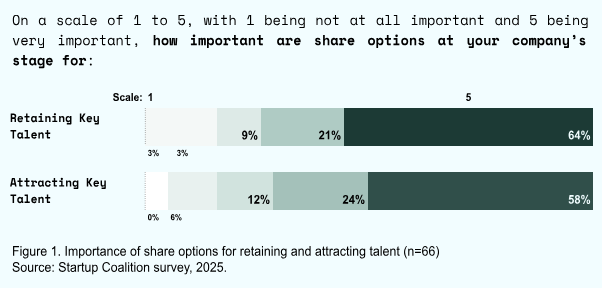

Options are essential infrastructure. When asked to rate the importance of share options on a scale of 1 to 5, the majority of respondents gave the highest rating. 82% of employers rated them as important for attracting top talent, and 85% for retention.

The stakes are high. 85% of employers agreed that staff motivation would suffer if share option benefits changed significantly, and 58% believed that some employees would likely leave if options became less attractive.

EMI makes it work. 92% of employers think EMI options are a meaningful motivator for their employees, and 82% agreed that EMI helps them attract talent they might otherwise struggle to hire.

They have also highlighted some key areas where the scheme falls short or could be improved:

First, setting up an EMI scheme and remaining compliant is an unnecessarily complicated process. Smaller companies – the ones EMI is specifically designed to help – can’t properly navigate it without significant legal and tax expertise that they often lack. The real consequences only emerge years later during exit events when due diligence reveals mistakes, non-compliance issues, and improper structures.

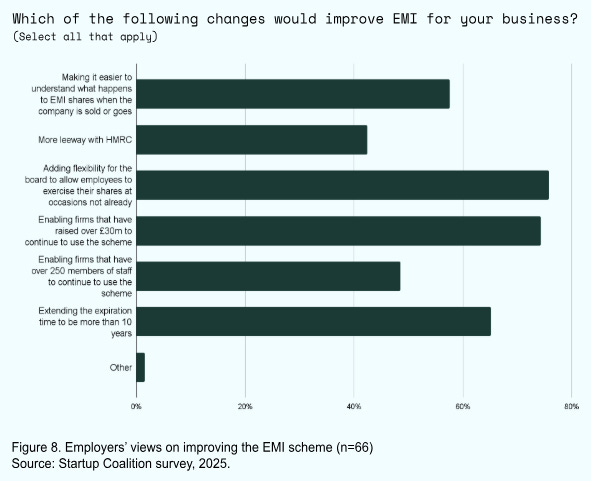

Employees who believed they held valuable EMI options can suddenly find themselves with unapproved options instead – facing dramatically higher tax bills and diminished equity value through no fault of their own. Over half of founders and executives said that ‘making it easier to understand what happens to EMI shares when the company is sold or goes public’ would improve EMI for their business.

Second, the scheme lacks flexibility when market conditions evolve. Traditional EMI agreements were designed around a world where companies typically exited within 10 years through IPO or acquisition. But as companies stay private for longer and new liquidity mechanisms emerge – most frequently secondary transactions where existing shareholders sell to new investors in private funding rounds – contracts, made rigid by new HMRC guidance, create a troubling asymmetry: other shareholders can access liquidity through these new mechanisms, while long-term employees remain locked out.

Founders said that the 10-year expiration date on the EMI scheme no longer tracks with their business plans – and it disproportionately affects the longest-serving employees, who are often the earliest joiners who took the biggest risks for the lowest salaries. If no liquidity event occurs within the 10-year window, these employees are forced to either risk losing their shares or exercise prematurely, converting what should have been a capital gain into income tax liability.

Recent data suggests the average time from startup founding to IPO now exceeds 10-12 years. Revolut, which was founded in 2015, is expected to IPO only this year or next. Deliveroo, founded in 2013, has only just been acquired this year.

From our own data, 16% of companies reported that their intended route to liquidity changed since designing their stock option scheme. Of those, 73% said they had significantly delayed or deprioritized their exit plans – often because continued private growth and access to capital made staying private more attractive than rushing to IPO.

Historically, companies have commonly used ‘Board discretion’ clauses in share option agreements as catch-alls, enabling the Board to create new opportunities for employees to sell their options when the environment shifts. For example, employers might enable an employee to sell their options before an exit if those options are coming up to their expiration date. However, HMRC has adopted an increasingly rigid interpretation requiring agreements to specify a ‘clear right of exercise from the outset’ – and it has been applied retroactively.

This traps the longest serving employees in a catch-22: their older contracts may lack the ‘clear right of exercise’ that newer employees enjoy, and their employer cannot use board discretion to help them exercise their options without risking EMI scheme disqualification.

Instead, highly valued employees are incentivised to leave companies they’ve devoted years to building.

70% of our respondents told us that they strongly agree that ‘The UK startup ecosystem would benefit if the EMI scheme’s time to expiry was extended beyond the current 10 years,’ with 81% in agreement overall.

76% of respondents said ‘adding flexibility for the Board to allow employees to exercise their shares at occasions not already included in share agreements’ would improve how EMI worked for their business.

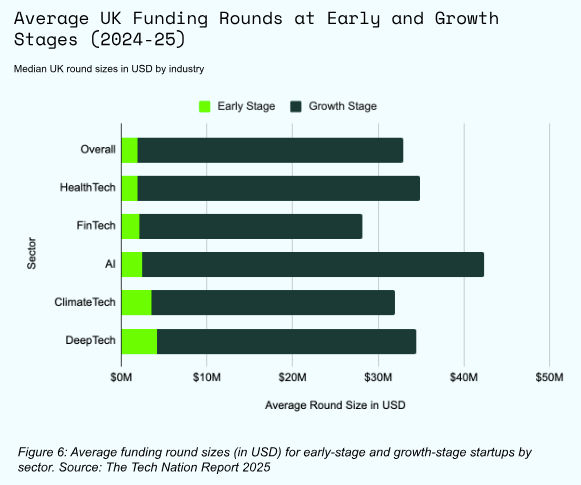

Third, EMI’s employee and asset caps have also not kept up with evolving growth patterns of the businesses they were designed to support. The data shows how dramatically growth patterns have shifted. In 2015–16, average growth-stage investments were around £7m. Today, TechNation puts the average at $31m (~£23m). For AI firms, the figures are even higher: average growth-stage funding now reaches $42.4m (~£31.5m), enough to breach EMI caps in a single round.

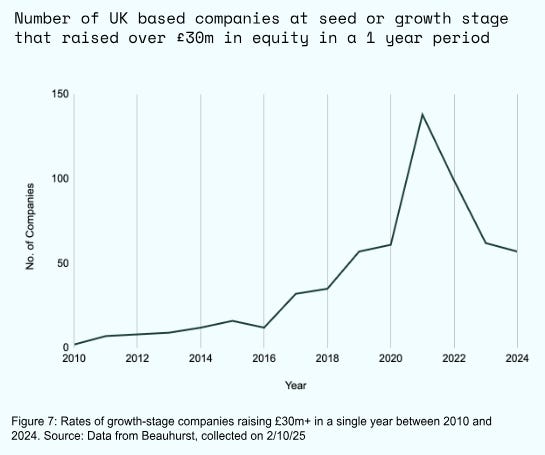

According to data from Beauhurst, the number of UK companies raising at least £30m in a single year has risen sharply – up 375% between 2014 and 2024, and an extraordinary 2,750% since 2010.

This growth can happen almost overnight. University College London spinout Synthesia raised £9m in April 2021 and a further £36.6m by November of the same year. Wayve secured £10m in October 2021 and another £147m just three months later.

When that funding round closes and pushes a company over the £30 million threshold, they don’t automatically transition to another scheme. They’re simply locked out of EMI for any future employees. While alternatives like the Company Share Option Plan (CSOP) exist, they are not always suitable or timely substitutes for EMI.

This leaves many successful UK scaleups in a policy no man’s land: too large for EMI but not yet at the scale where they can rely purely on cash compensation to attract top talent.

These scale-ups are often competing directly with Big Tech for senior hires while simultaneously trying to maintain the entrepreneurial culture and equity participation that drove their early success. They are losing a key tool to attract and retain talent precisely the moment companies need it most.

From our data:

74% of respondents wanted firms that have raised over £30m to be able to continue to use the scheme.

48% wanted firms that had surpassed 250 employees to be able to continue to use the scheme.

All of these problems can be huge issues for scaling firms – running counter to the intentions of EMI. They impact both the company trying to hire or keep talent in some of the world’s most competitive markets, and the employees who can find themselves in hot water when they have dedicated years to building a business but aren’t able to reap the financial rewards they were promised.

In a world where top talent is mobile, and where the best people can work from anywhere, outdated policy risks becoming a major liability. The UK remains a magnet for tech and founding talent. But if we don’t reform EMI, we risk losing the very people most likely to scale British companies and grow our economy.

To address these challenges, we have identified 5 changes that would improve the EMI scheme for founders and employees:

Simplify the Application Process: HMRC should review their website for ways to simplify the application and compliance process. Clear, accessible guidance would reduce administrative friction for both employers and employees.

Increase the Limits: The government should increase the current limits of EMI from a £30M asset cap to £150m and from 250 to 1000 employees. This reflects the scale of modern startups, accommodates larger funding rounds, and prevents companies from being penalised for growth.

Extend the Exercise Window: Extend the EMI exercise window to 15 years. Longer timelines align EMI with actual startup development cycles, rewarding early employees who took significant risk.

Allow Board Discretion: HMRC should allow Board discretion to extend exercise opportunities to employees when other shareholders access liquidity, without jeopardizing EMI qualification. HMRC guidance should explicitly permit Board discretion clauses that allow employees to exercise options when secondary transactions occur, other liquidity mechanisms emerge, or material changes to exit strategy occur.

Introduce ‘EMI Growth’: Because of the difficulties that can be caused when companies find themselves abruptly on the other side of a tax cliff, they need a scheme they can graduate onto smoothly when they do eventually outgrow EMI – one that doesn’t leave them scrambling to restructure their entire equity compensation approach while trying to close critical hires. A new ‘EMI Growth’ or ‘EMI Plus’ tier specifically designed for companies that have outgrown traditional EMI thresholds could have higher limits – e.g., £500M in assets and 2,500 employees – and could maintain tax advantages while accommodating larger, scaling firms.

This is a great piece and sets out many points that I've thought about when advising small and growing companies as a corporate solicitor.

My main issue though is with the existence of employment-related securities in the first place. That they exist adds layers of complications to companies that may be revenue-light or just starting up. For instance, if you want to bring on a new director into a company and you issue them shares so that they can have a stake in the company's profits, if they're issued for less than market value it attracts income tax. If you want to convert debt into equity to reduce the amount of debt in a company, if you issue too many shares then you risk an income tax liability.

The end result is that you force directors to either risk a massive income tax liability at some point in the future as HMRC is an unknowable and unpredictable beast to these people or you force small businesses to obtain legal and tax advice which can cost tens of thousands of pounds. Either way it's a penalty for taking a risk.